Possessive classifier systems are known to be ‘relational’: they signal the interaction between the possessor and the referent:

Lewo (Vanuatu; fieldwork data)

| 1a. | m̃a-u | mrawa |

|---|---|---|

| drink.cl-1sg | coconut | |

| ‘’my coconut (to drink)’’ | ||

| 1b. | ka-u | mrawa |

|---|---|---|

| food.cl-1sg | coconut | |

| ‘’my coconut (to eat)’’ | ||

Use of (1a) is appropriate if the possessor intends to drink the coconut, while (1b) would indicate an intention to eat it. These systems are well attested in Oceanic languages. They seem an unlikely source for gender-like systems, in which nouns canonically have fixed assignment. Yet Franjieh (2016, 2018) observes that North Ambrym is moving towards a system in which, for example, we ‘water’ is fixed as drink, just as in French eau ‘water’ is fixed as feminine. How can this come about?

Gender is a familiar reference tracking device. Possessive classifiers can also function for reference tracking without a possessed noun, across long stretches of discourse. We ask therefore how similar our classifiers are to a gender system. We describe a storyboard experiment (c.f., Burton & Matthewson 2015) with speakers of six Oceanic languages, including Lewo and North Ambrym (with an inventory size of classifiers from three to over twenty). We designed eight four-picture storyboards (Figure 1); each picture shows a different interaction with a particular object. By investigating the use of classifiers as reference tracking devices, we reveal their similarity to gender systems and the route of development from relational classifiers to gender.

Figure 1: Storyboard with different interactions (finding, carrying, roasting, selling).

Hypothesis: in languages with relational classifier systems (like Lewo), participants will use different classifiers for the antecedent noun, according to the interactions shown in the images. In languages with a more fixed system (like North Ambrym) however, we expect the same classifier to be used to mark the antecedent across the whole storyboard, thus showing a fixed gender-like system.

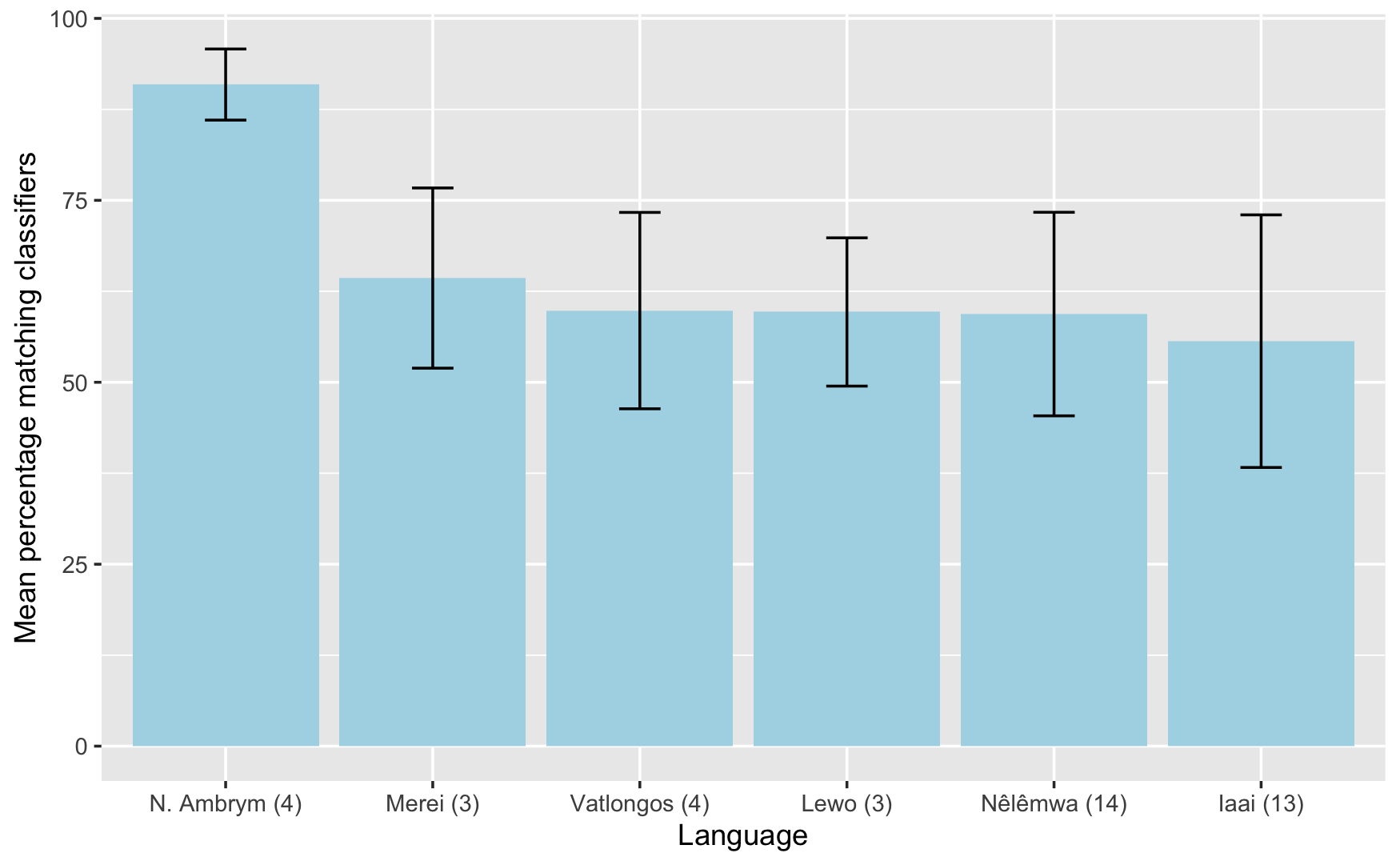

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare responses across languages. The number of identical classifier responses in a storyboard differed significantly across languages. Pairwise comparisons of individual languages indicated that North Ambrym had a significantly higher number of identical classifiers used in a storyboard than all other languages.

Our analyses show that North Ambrym’s system functions differently to the other languages in our sample, with the same classifier being used on average throughout a storyboard more than 90% of the time (Figure 2). The other languages in our sample retain typical relational classifier systems, whereas North Ambrym’s system closely resembles a fixed gender-like system.

Figure 2: Mean anaphoric agreement for each sample language (total number of classifiers given across all participants for each language in brackets). Standard error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Gender and classifiers were once thought of as disparate systems of categorisation but are now understood as belonging to a single typological space (Fedden & Corbett 2017). Our findings not only support a unified typology of nominal classification systems but provide critical evidence for the rise of agreement and gender systems from classifiers.

References

Burton, Strang and Matthewson, Lisa. 2015. Targeted Construction Storyboards in Semantic Fieldwork. In M. Ryan Bochnak and Lisa Matthewson (eds.), (2015), Methodologies in Semantic Fieldwork. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 135-156.

Fedden, Sebastian and Corbett, Greville G. 2017. Gender and classifiers in concurrent systems: Refining the typology of nominal classification. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics, 2(1:34), 1–47.

Franjieh, Michael. 2018. North Ambrym possessive classifiers from the perspective of canonical gender. In S. Fedden, J. Audring and G. Corbett (eds.) (2018), Non-canonical gender systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Franjieh, Michael. 2016. Indirect Possessive Hosts in North Ambrym: Evidence for Gender. Oceanic Linguistics 55:87-115.